8-12-2012 — /europawire.eu/ — TAX EVASION AND AVOIDANCE: Questions and Answers.

Tax Evasion

Why has the Commission presented an Action Plan on Tax fraud and evasion?

Every year, an estimated €1 trillion1 in public money is lost in the EU due to tax evasion and avoidance.

Member States suffer a serious loss of revenue, and a dent to the efficiency and fairness of their tax systems. Some businesses find themselves at a competitive disadvantage compared to those that find ways to avoid paying their fair share. The cross-border nature of tax evasion and avoidance, along with Member States’ concerns to maintain competitiveness, make it very difficult for purely national measures to have the full desired effect. Tax evasion is a multi-facetted problem requiring a multi-pronged approach, at national, EU and international level.

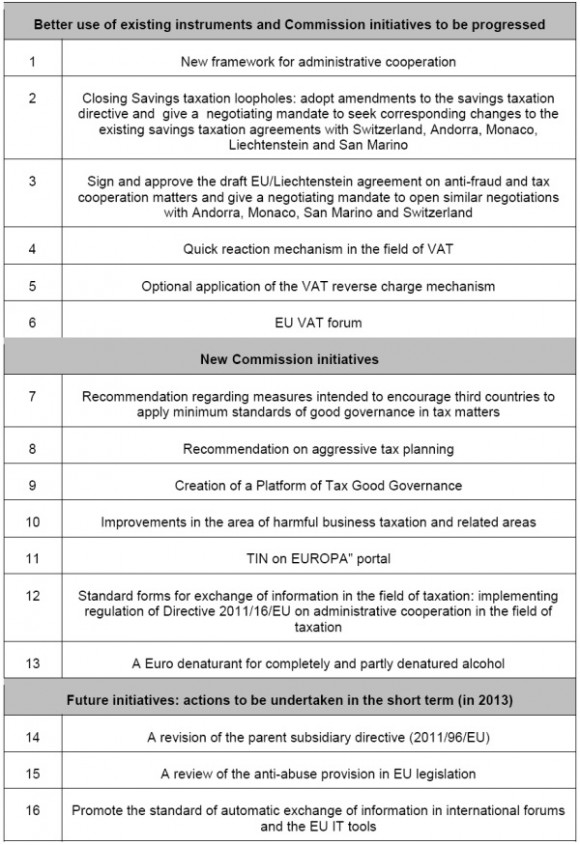

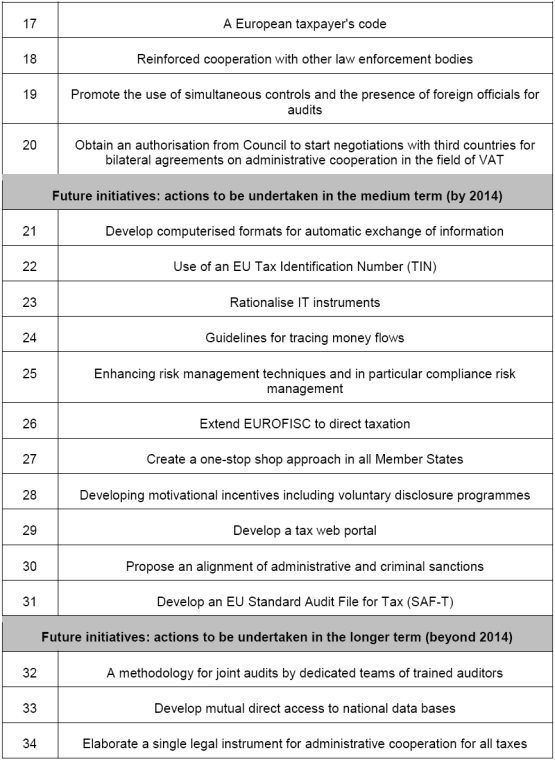

In March 2012, the 27 EU Heads of State asked the Commission to develop ideas and solutions to improve the fight against tax fraud and tax evasion. In April, the European Parliament also called for urgent action in this area. As a first response, the Commission adopted a Communication in June 2012 outlining how tax compliance could be improved and announced the preparation of today’s Action Plan (see IP/12/697 and MEMO/12/492). The Action Plan today contains over 30 measures to be developed now and in years to come. If all 27 EU Member States cooperate together, it will help to increase the fairness of their tax systems, secure much needed tax revenues and help to improve the proper functioning of the Single Market. In addition, the “strength in numbers” of the EU acting as a united block can carry much more weight in achieving faster and more ambitious progress at international level and in discussions with OECD and G20.

What measures are already in place in the EU to fight tax fraud and evasion?

The EU has built its standards of good governance in taxation on 3 pillars: transparency, information exchange, and fair tax competition. These are principles that must be respected by the Member States, and that the EU also seeks to promote internationally to the widest extent possible.

In terms of transparency and information exchange, administrative cooperation between Member States has been considerably strengthened in recent years. Thanks to EU rules in this field, national tax authorities benefit greatly from their mutual exchange of data, information and experiences, in order to better identify and address tax evasion and fraud. Important new legislation has been adopted in recent years to further strengthen administrative cooperation, including a new Directive on Administrative Cooperation which will enter into force on 1 January 2013. The EU Savings Directive is proof of the benefits of intra-EU cooperation. On average, information on 20 billion euros of taxable income is exchanged between Member States each year and five non-EU countries (including Switzerland and Liechtenstein) as well as ten dependent or associated territories of MS outside the EU (including Jersey, Guernsey, the Isle of Man, the Cayman Islands and Aruba) participate in the EU network of cooperation in this field through agreements providing for equivalent or the same measures as those of the EU Savings Directive.

To promote fair tax competition, the EU has the Code of Conduct on Business Taxation (see below). The Commission is currently in discussions with Switzerland and Liechtenstein to promote the principles of the Code beyond EU borders.

In June 2012, the Commission set out 25 concrete measures to fight more effectively, at national and EU level, against tax fraud and evasion (see IP/12/697). Some of these measures are already underway e.g. in July the Commission proposed a Quick Reaction Mechanism (QRM) against VAT fraud. The VAT strategy presented last December also looked specifically at how to tackle VAT fraud in better way.

In the Country Specific Recommendations for 2012, 10 Member States were encouraged to do more at national level to fight tax evasion and improve compliance. The Commission is always ready to provide targeted support and technical assistance to any Member State that needs it to strengthen its tax system against evasion, and improve tax collection.

What is set out in the Action Plan to strengthen the EU stance on evasion and avoidance?

As a starting point, Member States are urged to use, to full effect, the powerful tools already at their disposal. They should properly apply EU rules on administrative cooperation and information exchange, and rapidly agree on key proposals that could help recapture billions of euros. These include the revision of the EU Savings Tax Directive, a negotiating mandate to update the existing EU savings taxation agreements with Switzerland and other European third countries, and the Quick Reaction Mechanism to fight VAT fraud.

The Code of Conduct on Business Taxation should also be reinvigorated, to better address instances of harmful tax competition. Its scope could also be widened e.g. to cover wealthy individuals.

In the short term, EU measures will include a Taxpayers’ Code to improve compliance and standardised forms for information exchange. The Commission will review the anti-abuse provisions in the Directives on Parent-Subsidiary, Mergers and Interest and Royalties.

In the medium and long term, measures will include an EU Tax Identification Number (TIN), an EU tax web portal, guidelines for tracing money flows and possibly common sanctions for tax offences.

What is the Code of Conduct on Business Taxation?

The Code of Conduct is the EU’s main tool for ensuring fair tax competition in the area of business taxation. It sets out clear criteria for assessing whether or not a tax regime can be considered harmful. All Member States have committed to adhering to the principles of the Code. This means refraining from introducing tax measures deemed to be harmful and changing those that are found to be so. The Code of Conduct Group oversees the application of the Code, assesses regimes to determine whether or not they are harmful, and reports back to the EU’s Council of Finance Ministers on developments in this area at the end of each Presidency. Since the Code of Conduct was established in 1997, over 400 tax regimes have been assessed within the EU and the overseas countries and territories and around 100 have been eliminated when assessed as harmful.

The Code’s criteria for identifying harmful measures include:

- A significantly lower level of effective taxation than the general level of taxation in the country concerned (a tax benefit)

- Tax benefits reserved for non-residents or transactions with non-residents

- Tax benefits for activities which are isolated from the domestic economy and have no impact on the national tax base (ring-fencing)

- Tax benefits granted despite the absence of any real economic activity (substance)

- Departure from internationally accepted rules (especially OECD) in setting the basis of profit determination for companies in a multinational group

- Lack of transparency

What does the Action Plan say about the Code of Conduct in improving the EU’s fight against tax evasion and avoidance?

The criteria to be used to determine if a non-EU country is a “tax haven” or not will largely reflect those set out in the EU’s Code of Conduct (in addition to the OECD’s requirements on transparency and information exchange). This would send a clear signal that the EU expects its international partners to comply with the same minimum standards of good governance as Member States themselves comply with.

Beyond this, the Action Plan also calls on Member States to use the Code of Conduct to better effect, as part of the effort to tackle evasion and avoidance. To ensure that the Code meets its original goal of preventing harmful tax competition, the Commission recommends that, for example, Member States refer topics more quickly to Council for political decisions when necessary. In addition, the scope of the Code of Conduct should be expanded to include special tax regimes for wealthy individuals and which could be considered harmful to the Single Market.

How does the Commission intend to follow-up to the Action Plan?

The Commission will proceed in preparing the upcoming proposals and initiatives within the timeframe set out in the Action Plan. Already in the first half of 2013, it will launch consultations on the Taxpayers’ Code and work to promote EU good governance standards internationally, notably through the OECD. The Commission will also continue to push for rapid agreement amongst Member States of the important proposals already on the table, most notably the revised Savings Directive, negotiating mandates for stronger savings taxation agreements with Switzerland and others, and the Quick Reaction Mechanism for VAT fraud.

Beyond this, the Commission also intends to closely monitor the progress made by Member States in the implementation of today’s Recommendations and the work in relation to tax evasion, avoidance and tax havens. The Platform for Tax Good Governance will be established to provide the opportunity for regular feedback by Member States, and the Commission will maintain pressure when the momentum is considered to be insufficient. This continuous monitoring will feed into an official report within 3 years on the application of the recommended measures and their impact.

Tax Havens

What is the added value of a common EU approach to tax havens?

The criteria for identifying tax havens and measures to address them vary greatly from one Member State to another. This means that, in a Single Market, business and transactions involving tax havens can be routed through the Member States with the most lenient provisions. As a result, the real level of protection automatically coincides with the lowest common denominator i.e. those with a more ambitious approach are easily undermined in their efforts to clamp down on tax havens.

A common EU approach to defining and reacting to “tax havens” would therefore be much more effective than a patchwork of national approaches. A minimum standard applied by all Member States would prevent tax evaders and avoiders from taking advantage of different national approaches in order to access the “tax havens”.

Added to this, a common EU approach has “more bite”. It leaves third countries with no doubt about what is considered by Member States to be uncooperative behaviour, and the consequences of this. Acting as a block of 27 undoubtedly, representing 500 million citizens, has more weight than a series of unilateral measures.

Finally, with a strong, common approach the EU can continue to be a central player in the good governance campaign internationally. With the high standards it applies internally, and the robust criteria it applies in its relations with non-EU countries, it can push for more ambitious measures to be agreed globally through international forums such as the OECD.

What does the Commission recommend for a stronger, common approach on tax havens?

Member States are encouraged to adopt a common set of criteria to identify countries which do not respect minimum standards of good governance (“tax havens”). These criteria would help Member States to determine whether a non-EU country should be added to their national blacklists. Such common listing by all Member States in itself will send a strong signal. Additional measures which could be used in relation to non-compliant jurisdictions are also set out as part of the recommended common approach to tax havens.

The Commission also recommends positive measures that should be taken in relation to non-EU countries (particularly developing ones) committed to complying with the EU minimum standards of good governance.

What standards would apply in assessing whether a non-EU country should be considered a tax haven or not?

A non-EU country would be considered to comply with minimum standards of good governance if it effectively applied the OECD standards on transparency and information exchange, and did not operate harmful tax measures. The criteria used by EU Code of Conduct on Business Taxation would be the basis for assessing whether a non-EU country’s tax measures are harmful or not. Tax measures which give more favourable treatment to non-resident taxpayers than what is generally applied within that country would be considered potentially harmful, but there are other criteria as well. Examples would be offering a lower rate of corporate tax to foreign investors, or giving tax advantages to business operations that require no real economic activity or substantial presence within that country.

What would be the consequences for countries on Member States’ blacklists?

First of all, appearing on Member States’ blacklists would seriously undermine a jurisdiction’s reputation as a trustworthy and recognised international partner. Furthermore, Member States are encouraged to renegotiate, suspend or even terminate the Double Tax Convention (DTC) that they have with a blacklisted country. This could have serious consequences for the non-compliant jurisdiction. DTCs help to avoid double taxation and are valued highly by potential foreign investors, so a state without a DTC is much less attractive for investors. Essentially, it could become much less attractive for people and companies to use these jurisdictions to avoid taxes at home.

Beyond this, Member States are also advised to avoid promoting business with uncooperative jurisdictions and to take additional complementary actions where appropriate.

What positive measures does the Commission recommend Member States take to encourage compliance with EU good governance standards?

The Commission encourages Member States to use “carrots” as well as “sticks” in encouraging non-EU countries to comply with the EU good governance criteria. Countries which comply with the EU criteria should be removed from national blacklists, if they are on them, and Member States should consider concluding a DTC with these countries. They should also consider cooperating more closely with non-EU countries committed to complying with the EU standards, especially developing countries. This could include offering technical assistance e.g. by seconding tax experts, to those countries that want and would benefit from it.

How would the proposed EU approach differ from the current international (OECD) approach to tax havens?

The EU approach, which the Commission recommends, is based on three pillars of good governance: transparency, information exchange and fair competition. This goes further than the criteria currently applied internationally, which focus mainly just on the first two pillars.

On transparency and information exchange, the criteria in the Recommendation are the same as those applied within the OECD Global Forum on transparency and exchange of information. The Global Forum set certain standards and requirements for transparency and information exchange, which should be respected in order for a country to be considered as meeting the international standards. Through the Global Forum, an international peer review process is carried out to see whether the necessary rules and regulations are in place and working in each state. This peer review process is still on-going.

The main difference in the recommended EU approach lies in the criteria linked to “fair competition”. Member States would examine whether a non-EU country’s tax regime was in line with the principles of the EU’s Code of Conduct (see above), in assessing whether or not it should be blacklisted as a tax haven. This would encourage non-EU countries to respect the same high standards of good governance that apply within the EU itself.

Aggressive Tax Planning

What is “aggressive tax planning”?

Aggressive tax planning is when individuals or companies exploit legal technicalities of a tax system or mismatches between national tax systems with a deliberate intent to minimise the tax they pay. For example, aggressive tax planners may “treaty shop”, using the DTCs between different countries to escape taxation in any of these countries. Aggressive tax planning is usually done within the letter of the law, but does not respect the spirit of the law. It tends to stretch the interpretation of what is “legal” to the maximum extent, and minimise the taxes paid by the “planner” to a level below what could be seen as a fair share.

Why is the Commission putting specific focus on this problem?

Aggressive tax planning has become increasingly problematic for Member States for a number of reasons.

First, tax planning has taken on an inherently cross-border nature, and the changing shape of the economy has allowed tax planning to become ever more sophisticated. In a globalised economy, where tax bases are less tangible and more mobile, it has become impossible to impose effective national provisions against aggressive tax planning without the risk of businesses relocating. This is a cross-border problem that requires cross-border solutions.

Second, tax planners exploit mismatches and loopholes between national systems and different DTCs. Coordinated action is needed to close these loopholes and strengthen common defences.

Third, the economic crisis has led Member States –and their citizens – to re-examine their national tax systems closely. With ordinary citizens facing tax hikes and spending cuts across Europe, it is difficult to justify the fact that some manage to avoid paying their fair share simply because they have the means to engage in complex tax planning. Tackling aggressive tax planning can contribute to the overall fairness of a tax system.

Example: Profit participating loans are a type of loan which is often considered as debt in its country of source and as share capital in the country where the payment is made. This is a typical case of mismatch whereby two tax systems characterise the same payment differently for tax purposes. Taxpayers commonly arrange their tax affairs in a way that allows them to take advantage of this mismatch to benefit from (i) having the ‘interest’ deductible on one side of the border (state of source); and (ii) receiving a tax exempt ‘dividend’ on the other side of the border (state of residence).

What common measures could Member States apply to help to tackle aggressive tax planning?

Member States are encouraged to review their DTCs to ensure that they do not create opportunities to escape taxation completely. They should seek to include a clause in their DTCs (with each other and with non-EU countries) saying that they will only refrain from taxing certain income if it is taxed by the other contracting party. This would prevent double non-taxation.

Member States are also encouraged to adopt a common General Anti-Abuse Rule. This would allow them to ignore artificial arrangements used essentially for tax avoidance purposes and to tax on the basis of actual economic substance.

In addition, the Commission will seek to review the anti-abuse provisions in the Parent-Subsidiary, Interest and Royalties and Merger Directives to determine whether it should take action to strengthen these clauses in 2013.

Does corporate social responsibility have a role in reducing aggressive tax planning?

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) refers to actions taken by companies beyond their purely legal obligations, to contribute to society. The economic crisis and its social consequences have made Member States and citizens more aware of the need for fair burden sharing in consolidation efforts. Public attention has also become increasingly focused on the social and ethical performance of enterprises, including on issues such as the level of taxes they pay, bonuses and executive pay. The perception is that recovery efforts must take place on a two way street: Member States should support businesses in getting through the hard times, but equally businesses must contribute fairly to the recovery efforts. Aggressive tax avoidance can be considered contrary to the principles of corporate social responsibility (CSR). Paying taxes is one of the important positive impacts that enterprises have on the rest of society. Last year the Commission presented a package on CSR with measures to improve transparency and promote sustainable business among multinationals. This included more openness about taxes, royalties and bonuses paid worldwide (see IP/11/1238 and MEMO/11/730).

- Aortic Aneurysms: EU-funded Pandora Project Brings In-Silico Modelling to Aid Surgeons

- BREAKING NEWS: New Podcast “Spreading the Good BUZZ” Hosted by Josh and Heidi Case Launches July 7th with Explosive Global Reach and a Mission to Transform Lives Through Hope and Community in Recovery

- Cha Cha Cha kohtub krüptomaailmaga: Winz.io teeb koostööd Euroopa visionääri ja staari Käärijäga

- Digi Communications N.V. announces Conditional stock options granted to Executive Directors of the Company, for the year 2025, based on the general shareholders’ meeting approval from 25 June 20244

- Cha Cha Cha meets crypto: Winz.io partners with European visionary star Käärijä

- Digi Communications N.V. announces the exercise of conditional share options by the executive directors of the Company, for the year 2024, as approved by the Company’s OGSM from 25 June 2024

- “Su Fortuna Se Ha Construido A Base de La Defraudación Fiscal”: Críticas Resurgen Contra Ricardo Salinas en Medio de Nuevas Revelaciones Judiciales y Fiscaleso

- Digi Communications N.V. announces the availability of the instruction regarding the payment of share dividend for the 2024 financial year

- SOILRES project launches to revive Europe’s soils and future-proof farming

- Josh Case, ancien cadre d’ENGIE Amérique du Nord, PDG de Photosol US Renewable Energy et consultant d’EDF Amérique du Nord, engage aujourd’hui toute son énergie dans la lutte contre la dépendance

- Bizzy startet den AI Sales Agent in Deutschland: ein intelligenter Agent zur Automatisierung der Vertriebspipeline

- Bizzy lance son agent commercial en France : un assistant intelligent qui automatise la prospection

- Bizzy lancia l’AI Sales Agent in Italia: un agente intelligente che automatizza la pipeline di vendita

- Bizzy lanceert AI Sales Agent in Nederland: slimme assistent automatiseert de sales pipeline

- Bizzy startet AI Sales Agent in Österreich: ein smarter Agent, der die Sales-Pipeline automatisiert

- Bizzy wprowadza AI Sales Agent w Polsce: inteligentny agent, który automatyzuje budowę lejka sprzedaży

- Bizzy lanza su AI Sales Agent en España: un agente inteligente que automatiza la generación del pipeline de ventas

- Bizzy launches AI Sales Agent in the UK: a smart assistant that automates sales pipeline generation

- As Sober.Buzz Community Explodes Its Growth Globally it is Announcing “Spreading the Good BUZZ” Podcast Hosted by Josh Case Debuting July 7th

- Digi Communications N.V. announces the OGMS resolutions and the availability of the approved 2024 Annual Report

- Escándalo Judicial en Aumento Alarma a la Opinión Pública: Suprema Corte de México Enfrenta Acusaciones de Favoritismo hacia el Aspirante a Magnate Ricardo Salinas Pliego

- Winz.io Named AskGamblers’ Best Casino 2025

- Kissflow Doubles Down on Germany as a Strategic Growth Market with New AI Features and Enterprise Focus

- Digi Communications N.V. announces Share transaction made by a Non-Executive Director of the Company with class B shares

- Salinas Pliego Intenta Frenar Investigaciones Financieras: UIF y Expertos en Corrupción Prenden Alarmas

- Digital integrity at risk: EU Initiative to strengthen the Right to be forgotten gains momentum

- Orden Propuesta De Arresto E Incautación Contra Ricardo Salinas En Corte De EE.UU

- Digi Communications N.V. announced that Serghei Bulgac, CEO and Executive Director, sold 15,000 class B shares of the company’s stock

- PFMcrypto lancia un sistema di ottimizzazione del reddito basato sull’intelligenza artificiale: il mining di Bitcoin non è mai stato così facile

- Azteca Comunicaciones en Quiebra en Colombia: ¿Un Presagio para Banco Azteca?

- OptiSigns anuncia su expansión Europea

- OptiSigns annonce son expansion européenne

- OptiSigns kündigt europäische Expansion an

- OptiSigns Announces European Expansion

- Digi Communications NV announces release of Q1 2025 financial report

- Banco Azteca y Ricardo Salinas Pliego: Nuevas Revelaciones Aumentan la Preocupación por Riesgos Legales y Financieros

- Digi Communications NV announces Investors Call for the presentation of the Q1 2025 Financial Results

- Digi Communications N.V. announces the publication of the 2024 Annual Financial Report and convocation of the Company’s general shareholders meeting for June 18, 2025, for the approval of, among others, the 2024 Annual Financial Report, available on the Company’s website

- La Suprema Corte Sanciona a Ricardo Salinas de Grupo Elektra por Obstrucción Legal

- Digi Communications N.V. announces the conclusion of an Incremental to the Senior Facilities Agreement dated 21 April 2023

- 5P Europe Foundation: New Initiative for African Children

- 28-Mar-2025: Digi Communications N.V. announces the conclusion of Facilities Agreements by companies within Digi Group

- Aeroluxe Expeditions Enters U.S. Market with High-Touch Private Jet Journeys—At a More Accessible Price ↗️

- SABIO GROUP TAKES IT’S ‘DISRUPT’ CX PROGRAMME ACROSS EUROPE

- EU must invest in high-quality journalism and fact-checking tools to stop disinformation

- ¿Está Banco Azteca al borde de la quiebra o de una intervención gubernamental? Preocupaciones crecientes sobre la inestabilidad financiera

- Netmore and Zenze Partner to Deploy LoRaWAN® Networks for Cargo and Asset Monitoring at Ports and Terminals Worldwide

- Rise Point Capital: Co-investing with Independent Sponsors to Unlock International Investment Opportunities

- Netmore Launches Metering-as-a-Service to Accelerate Smart Metering for Water and Gas Utilities

- Digi Communications N.V. announces that a share transaction was made by a Non-Executive Director of the Company with class B shares

- La Ballata del Trasimeno: Il Mediometraggio si Trasforma in Mini Serie

- Digi Communications NV Announces Availability of 2024 Preliminary Financial Report

- Digi Communications N.V. announces the recent evolution and performance of the Company’s subsidiary in Spain

- BevZero Equipment Sales and Distribution Enhances Dealcoholization Capabilities with New ClearAlc 300 l/h Demonstration Unit in Spain Facility

- Digi Communications NV announces Investors Call for the presentation of the 2024 Preliminary Financial Results

- Reuters webinar: Omnibus regulation Reuters post-analysis

- Patients as Partners® Europe Launches the 9th Annual Event with 2025 Keynotes, Featured Speakers and Topics

- eVTOLUTION: Pioneering the Future of Urban Air Mobility

- Reuters webinar: Effective Sustainability Data Governance

- Las acusaciones de fraude contra Ricardo Salinas no son nuevas: una perspectiva histórica sobre los problemas legales del multimillonario

- Digi Communications N.V. Announces the release of the Financial Calendar for 2025

- USA Court Lambasts Ricardo Salinas Pliego For Contempt Of Court Order

- 3D Electronics: A New Frontier of Product Differentiation, Thinks IDTechEx

- Ringier Axel Springer Polska Faces Lawsuit for Over PLN 54 million

- Digi Communications N.V. announces the availability of the report on corporate income tax information for the financial year ending December 31, 2023

- Unlocking the Multi-Million-Dollar Opportunities in Quantum Computing

- Digi Communications N.V. Announces the Conclusion of Facilities Agreements by Companies within Digi Group

- The Hidden Gem of Deep Plane Facelifts

- KAZANU: Redefining Naturist Hospitality in Saint Martin ↗️

- New IDTechEx Report Predicts Regulatory Shifts Will Transform the Electric Light Commercial Vehicle Market

- Almost 1 in 4 Planes Sold in 2045 to be Battery Electric, Finds IDTechEx Sustainable Aviation Market Report

- Digi Communications N.V. announces the release of Q3 2024 financial results

- Digi Communications NV announces Investors Call for the presentation of the Q3 2024 Financial Results

- Pilot and Electriq Global announce collaboration to explore deployment of proprietary hydrogen transport, storage and power generation technology

- Digi Communications N.V. announces the conclusion of a Memorandum of Understanding by its subsidiary in Romania

- Digi Communications N.V. announces that the Company’s Portuguese subsidiary finalised the transaction with LORCA JVCO Limited

- Digi Communications N.V. announces that the Portuguese Competition Authority has granted clearance for the share purchase agreement concluded by the Company’s subsidiary in Portugal

- OMRON Healthcare introduceert nieuwe bloeddrukmeters met AI-aangedreven AFib-detectietechnologie; lancering in Europa september 2024

- OMRON Healthcare dévoile de nouveaux tensiomètres dotés d’une technologie de détection de la fibrillation auriculaire alimentée par l’IA, lancés en Europe en septembre 2024

- OMRON Healthcare presenta i nuovi misuratori della pressione sanguigna con tecnologia di rilevamento della fibrillazione atriale (AFib) basata sull’IA, in arrivo in Europa a settembre 2024

- OMRON Healthcare presenta los nuevos tensiómetros con tecnología de detección de fibrilación auricular (FA) e inteligencia artificial (IA), que se lanzarán en Europa en septiembre de 2024

- Alegerile din Moldova din 2024: O Bătălie pentru Democrație Împotriva Dezinformării

- Northcrest Developments launches design competition to reimagine 2-km former airport Runway into a vibrant pedestrianized corridor, shaping a new era of placemaking on an international scale

- The Road to Sustainable Electric Motors for EVs: IDTechEx Analyzes Key Factors

- Infrared Technology Breakthroughs Paving the Way for a US$500 Million Market, Says IDTechEx Report

- MegaFair Revolutionizes the iGaming Industry with Skill-Based Games

- European Commission Evaluates Poland’s Media Adherence to the Right to be Forgotten

- Global Race for Autonomous Trucks: Europe a Critical Region Transport Transformation

- Digi Communications N.V. confirms the full redemption of €450,000,000 Senior Secured Notes

- AT&T Obtiene Sentencia Contra Grupo Salinas Telecom, Propiedad de Ricardo Salinas, Sus Abogados se Retiran Mientras Él Mueve Activos Fuera de EE.UU. para Evitar Pagar la Sentencia

- Global Outlook for the Challenging Autonomous Bus and Roboshuttle Markets

- Evolving Brain-Computer Interface Market More Than Just Elon Musk’s Neuralink, Reports IDTechEx

- Latin Trails Wraps Up a Successful 3rd Quarter with Prestigious LATA Sustainability Award and Expands Conservation Initiatives ↗️

- Astor Asset Management 3 Ltd leitet Untersuchung für potenzielle Sammelklage gegen Ricardo Benjamín Salinas Pliego von Grupo ELEKTRA wegen Marktmanipulation und Wertpapierbetrug ein

- Digi Communications N.V. announces that the Company’s Romanian subsidiary exercised its right to redeem the Senior Secured Notes due in 2025 in principal amount of €450,000,000

- Astor Asset Management 3 Ltd Inicia Investigación de Demanda Colectiva Contra Ricardo Benjamín Salinas Pliego de Grupo ELEKTRA por Manipulación de Acciones y Fraude en Valores

- Astor Asset Management 3 Ltd Initiating Class Action Lawsuit Inquiry Against Ricardo Benjamín Salinas Pliego of Grupo ELEKTRA for Stock Manipulation & Securities Fraud

- Digi Communications N.V. announced that its Spanish subsidiary, Digi Spain Telecom S.L.U., has completed the first stage of selling a Fibre-to-the-Home (FTTH) network in 12 Spanish provinces

- Natural Cotton Color lancia la collezione "Calunga" a Milano

- Astor Asset Management 3 Ltd: Salinas Pliego Incumple Préstamo de $110 Millones USD y Viola Regulaciones Mexicanas

- Astor Asset Management 3 Ltd: Salinas Pliego Verstößt gegen Darlehensvertrag über 110 Mio. USD und Mexikanische Wertpapiergesetze

- ChargeEuropa zamyka rundę finansowania, której przewodził fundusz Shift4Good tym samym dokonując historycznej francuskiej inwestycji w polski sektor elektromobilności

- Strengthening EU Protections: Robert Szustkowski calls for safeguarding EU citizens’ rights to dignity

- Digi Communications NV announces the release of H1 2024 Financial Results

- Digi Communications N.V. announces that conditional stock options were granted to a director of the Company’s Romanian Subsidiary

- Digi Communications N.V. announces Investors Call for the presentation of the H1 2024 Financial Results

- Digi Communications N.V. announces the conclusion of a share purchase agreement by its subsidiary in Portugal

- Digi Communications N.V. Announces Rating Assigned by Fitch Ratings to Digi Communications N.V.

- Digi Communications N.V. announces significant agreements concluded by the Company’s subsidiaries in Spain

- SGW Global Appoints Telcomdis as the Official European Distributor for Motorola Nursery and Motorola Sound Products

- Digi Communications N.V. announces the availability of the instruction regarding the payment of share dividend for the 2023 financial year

- Digi Communications N.V. announces the exercise of conditional share options by the executive directors of the Company, for the year 2023, as approved by the Company’s Ordinary General Shareholders’ Meetings from 18th May 2021 and 28th December 2022

- Digi Communications N.V. announces the granting of conditional stock options to Executive Directors of the Company based on the general shareholders’ meeting approval from 25 June 2024

- Digi Communications N.V. announces the OGMS resolutions and the availability of the approved 2023 Annual Report

- Czech Composer Tatiana Mikova Presents Her String Quartet ‘In Modo Lidico’ at Carnegie Hall

- SWIFTT: A Copernicus-based forest management tool to map, mitigate, and prevent the main threats to EU forests

- WickedBet Unveils Exciting Euro 2024 Promotion with Boosted Odds

- Museum of Unrest: a new space for activism, art and design

- Digi Communications N.V. announces the conclusion of a Senior Facility Agreement by companies within Digi Group

- Digi Communications N.V. announces the agreements concluded by Digi Romania (formerly named RCS & RDS S.A.), the Romanian subsidiary of the Company

- Green Light for Henri Hotel, Restaurants and Shops in the “Alter Fischereihafen” (Old Fishing Port) in Cuxhaven, opening Summer 2026

- Digi Communications N.V. reports consolidated revenues and other income of EUR 447 million, adjusted EBITDA (excluding IFRS 16) of EUR 140 million for Q1 2024

- Digi Communications announces the conclusion of Facilities Agreements by companies from Digi Group

- Digi Communications N.V. Announces the convocation of the Company’s general shareholders meeting for 25 June 2024 for the approval of, among others, the 2023 Annual Report

- Digi Communications NV announces Investors Call for the presentation of the Q1 2024 Financial Results

- Digi Communications intends to propose to shareholders the distribution of dividends for the fiscal year 2023 at the upcoming General Meeting of Shareholders, which shall take place in June 2024

- Digi Communications N.V. announces the availability of the Romanian version of the 2023 Annual Report

- Digi Communications N.V. announces the availability of the 2023 Annual Report

- International Airlines Group adopts Airline Economics by Skailark ↗️

- BevZero Spain Enhances Sustainability Efforts with Installation of Solar Panels at Production Facility

- Digi Communications N.V. announces share transaction made by an Executive Director of the Company with class B shares

- BevZero South Africa Achieves FSSC 22000 Food Safety Certification

- Digi Communications N.V.: Digi Spain Enters Agreement to Sell FTTH Network to International Investors for Up to EUR 750 Million

- Patients as Partners® Europe Announces the Launch of 8th Annual Meeting with 2024 Keynotes and Topics

- driveMybox continues its international expansion: Hungary as a new strategic location

- Monesave introduces Socialised budgeting: Meet the app quietly revolutionising how users budget

- Digi Communications NV announces the release of the 2023 Preliminary Financial Results

- Digi Communications NV announces Investors Call for the presentation of the 2023 Preliminary Financial Results

- Lensa, един от най-ценените търговци на оптика в Румъния, пристига в България. Първият шоурум е открит в София

- Criando o futuro: desenvolvimento da AENO no mercado de consumo em Portugal

- Digi Communications N.V. Announces the release of the Financial Calendar for 2024

- Customer Data Platform Industry Attracts New Participants: CDP Institute Report

- eCarsTrade annonce Dirk Van Roost au poste de Directeur Administratif et Financier: une décision stratégique pour la croissance à venir

- BevZero Announces Strategic Partnership with TOMSA Desil to Distribute equipment for sustainability in the wine industry, as well as the development of Next-Gen Dealcoholization technology

- Editor's pick archive....